For those not in the know, the killing fields represent thousands of rural locations throughout Cambodia where horrible, unthinkable atrocities against humanity took place. In 1975, Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge regime took control of Cambodia, forcing everyone out of the cities and into the countryside. In the name of creating a classless society of working peasants (who could be “yes” men), he quickly went to work “cleansing” the country, killing anyone who had any hint of intelligence or culture, as well as foreigners of any kind: teachers, doctors, lawyers, students, artists, dancers, and more, in a massive genocide that killed an estimated 3 million men, women, and children (by UNICEF’s estimates), about one-third of the country’s entire population. The torture and violence did not end until 1979, when Pol Pot was run into the jungle by the Vietnamese.

For those not in the know, the killing fields represent thousands of rural locations throughout Cambodia where horrible, unthinkable atrocities against humanity took place. In 1975, Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge regime took control of Cambodia, forcing everyone out of the cities and into the countryside. In the name of creating a classless society of working peasants (who could be “yes” men), he quickly went to work “cleansing” the country, killing anyone who had any hint of intelligence or culture, as well as foreigners of any kind: teachers, doctors, lawyers, students, artists, dancers, and more, in a massive genocide that killed an estimated 3 million men, women, and children (by UNICEF’s estimates), about one-third of the country’s entire population. The torture and violence did not end until 1979, when Pol Pot was run into the jungle by the Vietnamese.

To get a sense of life under his regime, when institutions such as marriage, family, education, music, and more were outlawed, see Seth Mydan’s obituary of Pol Pot for the New York Times.

Today, Cambodia still struggles to get out from under this crippling loss. In Phnom Penh, we watched a beautiful traditional dance, the art of which is being “recovered” by the few still alive who can remember and teach this art form (see Cambodian Living Arts for more information). I also interviewed CNN Hero, Ponheary Ly, who herself suffered in prison and lost 12 members of her family under the Khmer Rouge. She now works tirelessly to give rural children an education and hope for a better life. “It’s hard to hire qualified teachers when the intelligentsia has been wiped out,” her business partner, Lori Carlson, told me. And in Penang, Malaysia, at the Georgetown Festival, I met Rithy Panh, a Cambodian filmmaker whose work has been nominated for an academy award. I asked him how he was able to get his latest film (The Missing Picture) done, given that virtually no one in his country was left who knew how to create film or art. “I trained every crew member myself,” he explained. The patience, dedication, and persistence in pursuing one’s art in the face of such odds speaks volumes to the drive to bring back culture, art, and humanity to Cambodia.

In the outskirts of Siam Reap, we saw some of the most exquisite temples and ruins in all of Southeast Asia, including the famous Angkor Wat, but their restoration and existence depends on the help of other nations. Some archways are held up so rickety with sticks I forbade our kids to enter them. Cambodia is very slowly getting back on its feet, but not without the help of numerous NGOs, who are part of the country’s current fabric.

Bearing Witness

Thus, to truly understand today’s Cambodia, I felt it important to bear witness to the atrocities of its past and visit the memorialized Killing Fields of Choeung Ek, located nine miles outside the capital city of Phnom Penh and representative of the thousands that existed at the time just like it. I also planned to visit Phnom Penh’s Genocide Museum, the former Tuol Sleng Prison (which was before that a high school), where prisoners were tortured and killed.

Although we took our kids to the War Museum in Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), my husband Pierre held the kids back from these two sights, letting me visit on my own. A good choice, I think, especially for the Tuol Sleng Prison, which is so graphic in its depictions of torture and other horrors.

The Killing Fields of Choeung Ek

For about $ 20 U.S., we hired our hotel staff’s tuk-tuk (and driver) for the day. We first headed to the Killing Fields of Choeung Ek, which is now a memorial to the atrocities there, nine miles outside Phnom Penh, at around 8 a.m. When we arrived, Pierre took our kids to one of the street side restaurants to hang out while I took my time exploring the sight.

Your entry ticket ($ 6 U.S.; children under 12 are free) includes the audio program in your language, which you can’t really do without. Wandering among the grounds, you wouldn’t know what’s what just by looking at it, necessarily, with the exception of the commemorative four-story glass monument filled with hundreds of skulls. Also, listening to the voices of survivors sharing the history of how Pol Pot came to be, how life changed afterward, and their own moving, personal accounts of rape, torture, killings, betrayal, and more, along with an account from one of the guards, is deeply arresting and emotional.

Thankfully, benches throughout the sight allow visitors to sit and listen, pause and reflect. There was a couple on one bench huddled together, listening intently, and on another, a middle-aged woman sat, quietly sobbing.

Exhibits include sunken grounds where hundreds of bodies were piled, the weigh station where people were roughly chained until it was their time to die, the loud speaker that would sing songs or say prayers loudly at full blast at night to muffle the screams of the dying, a glass box full of the clothes of victims that were found in the fields much later, and most tragically, the Killing Tree, which was used to kill babies and small children, usually by clutching their feet and whacking their heads against the tree. What Pol Pot said to have the guards kill children too: “You must start at the root to clear the grass.” Today, the Killing Tree is adorned with thousands of colorful bracelets in commemoration.

I thought what I believe most visitors think: How could any human being do such atrocious things to another human being? And: We must never let this happen again.

The final exhibit is the Memorial Stupa, or tower of skulls. It not only includes skulls from victims of this sight, but describes how particular people were killed based on injuries to their skull, and with what tool. Bullets were considered expensive, so the barbaric tools used include axes, hoes, sticks, clubs, and more.

In a daze, I returned the audio equipment and left to meet up with my family, happy to be in the present day with loved ones. We returned to Phnom Penh for lunch, and then headed to the Genocide Museum.

The Genocide Museum: Tuol Sleng Prison

In the afternoon, our tuk-tuk driver took us to the Genocide Museum (tickets $3 U.S.), which was the Tuol Sleng Prison, a place where 14,000 were imprisoned, tortured, and killed, with only seven known to have survived the ordeal. On the day of my visit, one of those rare survivors was selling his memoirs on the property. Knowing what I know now about the place, I wouldn’t have had the guts to come anywhere near the place afterwards.

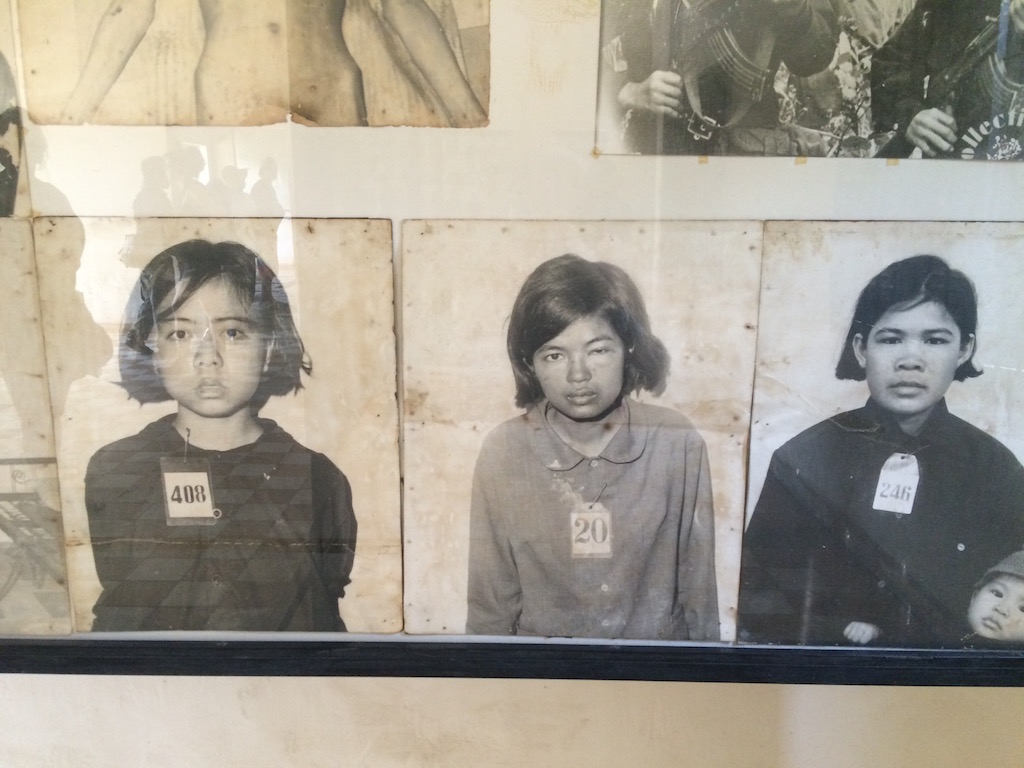

Unlike the killing fields, in which the horrors were revealed largely in audio stories, the Genocide Museum presented graphic photos and artworks of unimaginable acts of torture and killing of men, women, and children. The looks on victims’ faces—gaunt, terrified, resigned, pained, shocked—was haunting, especially knowing that they were all going to suffer greatly and die, even the young woman holding her baby tight to her chest. Most of these visual documents were created during the time itself, a way to prove to the regime that staff was carrying out its orders.

After wandering through three of the dozens of bare, gray rooms with photos of victims, including an Australian aid worker, exhibits of explicit torture, and stories of how the prison was run, with back stories on some of the victims, I was done. I couldn’t stomach any more. The atrocities became a fire in my belly I had to put out.

I smiled at my family, waiting in the courtyard for me. “I’m done. Let’s go,” I said.

Compassion for Humanity

Pierre doesn’t believe in seeing such sights. Even with car crashes, he turns away. “It just makes me feel sad and sick, and there’s nothing I can do to help.”

But I believe in looking into the eyes of past atrocities in order to learn from them so that, one hopes, we can be aware to not repeat the same mistakes in the future. But sadly, history has a way of repeating itself. Even as I write this, atrocities are happening in the world (right now, in Aleppo).

In the end, what I mostly gained from visiting these sights is greater compassion and understanding, not only for the people of Cambodia, but for humanity, and that’s not nothing.

This blog post, including photos, is copyrighted (c) 2016 by Cindy Bailey Giauque and is an original publication of www.mylittlevagabonds.com. Please join us on Twitter and Facebook. Happy travels!

What a powerful, tough experience. I’m like you. I need to visit places like the Killing Fields. It’s so hard to fathom that anybody can do this – and that we don’t learn from our mistakes and do it again and again. The latest in Aleppo. Thank you for honoring the victims and having greater compassion and understanding. It has to help.

Thank you, Betty! I, too, cannot fathom how anyone can do such things to another human. More compassion is always a good thing.

Mrs. Giauque:

I came across your website “mylittlevagabonds” as I searched the internet to verify a footnote to a reference in what, hopefully, will be a novel about Amerasian Children who are/were products of American servicemen and Vietnamese women during the Vietnam War. The lady writing the novel was born during this time period in North Vietnam and later moved to the South with her parents where she was raised in the Mekong Delta. I was fortunate enough to become acquainted with her last year when after 50 years I found that I could no longer deal with not knowing if I had a child in Vietnam or not. This lady has a passion in life to bring to light not only the plight of the Amerasian Child but also of the mother and father. But this is not the reason I am commenting on your page.

After coming home from Vietnam in April of 1966 I seem to have lost contact with the world during the rest of the 60’s and the 70’s although during this time period I met my future wife (and we will be married 50 years this July 19th), started my family, graduated from college and many other events but I have no knowledge of the atrocities of the Cambodian people you have described here.

Could I be so blind or could the world be so blind that we do not/did not know this was going on? Or that it is going on somewhere today. God help us!

I want to know more about this and I will search and read what I find and I would like to be kept abreast of your travels and findings.

Thank you for a very informative website.

Thank you, Herman. It sounds like you have quite a story and connection with Vietnam! Yes, what happened in Cambodia was horrible. I wish we would learn from our mistakes. Thanks for reading!