When we planned our visit to Vietnam, I admit that I didn’t know much about this culturally rich country other than they make great Pho (noodle soup) and were part of a massive thorn in America’s political-historical side: the Vietnam War. My only impressions came from the many Hollywood movies that I’d seen about that war.

When we planned our visit to Vietnam, I admit that I didn’t know much about this culturally rich country other than they make great Pho (noodle soup) and were part of a massive thorn in America’s political-historical side: the Vietnam War. My only impressions came from the many Hollywood movies that I’d seen about that war.

So, I was excited to visit Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), which many locals still refer to as Saigon (and in fact, the downtown area is still called Saigon), and find out what the real Vietnam is all about. In having our son do a homeschooling report, I learned that Vietnam has a politically complicated history and, sadly, has seen a lot of war. First, there was the Chinese, who occupied the Vietnamese for 1,000 years, and later came the French in the late 19th century to colonize Vietnam, along with Laos and Cambodia, into what was then called Indochina. After complications that involved other nations following World War II, the Vietnamese finally squeezed the French out in 1956, although they were left with some of their colonial buildings and kept their French bread, widely used today in sandwiches called Banh Mi, among other French influences that remain.

And finally, there were the Americans. Originally, it was the French who broke Vietnam into pieces: the north, the center, and the south, and a guide we hired would tell us that even today, all three regions are different from each other in attitudes, culture, and foods. The country would later be united under Ho Chi Minh’s communist leadership, and then divided again into north and south, again by the French who claimed the south as theirs, leaving the north to Ho Chi Minh.

Americans had been financially aiding the French against North Vietnam for many years already. To simplify what happened next: When the French finally left, the north wanted to reunify the country under communism and the south, largely supported by the U.S., resisted. Americans felt it in their best interest at the time to aid the south in fighting against the growing threat of communism represented by North Vietnam.

(For a far better and much more fascinating rendition of Vietnam’s history, check out this BBC documentary. More are available at this link.)

So, important to our stay in HCMC, then, would be a visit to the War Remnants Museum as well as the Cu Chi tunnels, a large network of underground tunnels the Vietcong had built to hide in and fight from. We wanted to see for ourselves what the war was like for Vietnam.

War Remnants Museum

Although you can find remnants of war, such as captured U.S. fighter jets and old prisons, throughout Vietnam, I don’t believe any of it is as deeply affecting as The War Remnants Museum in HCMC/Saigon.

You have to know going in, though, that it’s an unbalanced look at the Vietnam-American War, which the Vietnamese call the War of Aggression, the American War, or the War of Resistance (from the Americans). What we know as the “Fall of Saigon” on April 30, 1975 is called “Reunification Day” in Vietnam. The museum depicts in graphic detail, and choreographs for heightened effect, the horrific atrocities caused by Americans, with no mention of violent acts by the Vietcong or North Vietnam soldiers.

Nevertheless, there is no denying those horrific atrocities occurred, and, especially if you’re an American, it can be very hard to take.

I moved through the museum slowly, trying hard not to cry or vomit at the graphic images of both war and its aftermath.

The first floor started innocently enough with sharing images and quotes to show that the whole world, including Americans at home, were against America’s participation in this war. Part of the exhibits: the monk who burned himself in protest against the war and a Japanese man who did the same.

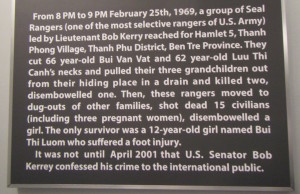

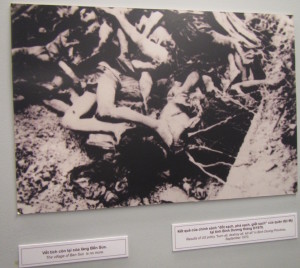

The second floor gets nasty with gut-wrenching images and stories of Vietnamese women, children, and civilians being killed by Americans. Prominently featured is the horrific My Lai Massacre that involved the brutal killings of over 300 civilians, including women and children, at the hands of Americans, with a small space on the wall for the two American pilots that managed to save 10 civilians during this unthinkable act.

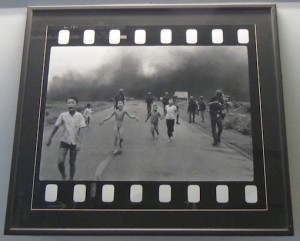

The famous pulitzer-prize winning photos of Kim Pham Luc (Kim Phuc) were there, as well as stories of GIs killing children in the fields. What was particularly nasty is the depiction of chemicals used, the napalm bombs that burned, and the defoliant, Agent Orange, which is still mutilating people through generations today.

This was featured as part of the after-effects. After Americans left, the mines, bombs, and explosives stayed behind and continued to kill others by accident. And then there was the previously mentioned Agent Orange, a chemical developed by Monsanto (that’s right, maker of our genetically-modified soybean today) to clear vegetation and enable soldiers to see the enemy fight. Exhibits share that parts of the soil today still contain levels of dioxins that are 300% the level for healthy tolerance.

Those directly affected got cancer and gave birth to malformed children for generations to come. Seeing the photos of babies with bulging eyes and children with missing limbs or swollen heads was especially hard to handle. The museum included one photo of a little white girl, born with no left arm. She was the daughter of an American Vietnam Vet who developed cancer and PTSD and eventually committed suicide. (I would the next day meet an American whose father was a vet and a victim of Agent Orange. He is only one of two out of seven in his unit that is still alive, and he has cancer and suffers terribly.)

UGLY.

I was almost relieved to make it to the top floor, which was about “peace and healing.” It was a tribute to the 73 photographers who lost their lives in the war. There were still sad stories to be told, but after the visual carnage in the other rooms, this felt like a relief, a surrender, to the events of war.

Outside afterward, I wandered in a stupor with my husband Pierre, photographing the tanks and aircraft while our two kids played in the play area inside. (As it turned out, they weren’t really interested in the exhibit, which didn’t mean anything to them and in fact, bored them.) Sitting outside, I saw a Vietnamese man selling his stack of guidebooks. He had one arm and one leg and I immediately thought, “Agent Orange.” As I passed him, he asked me where I was from. Having just seen the butchery by the Americans against the Vietnamese, in the way the museum presented it, I hesitated. I really wanted to say that I was Canadian (which I am, by birth), but decided to own up to who I am and said, “I am American.” He said simply, “Oh, Happy New Year!” as it was early January.

Cu Chi Tunnels

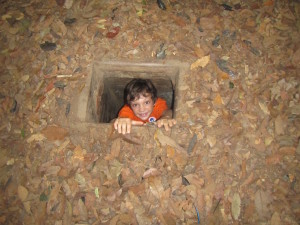

The Cu Chi tunnels proved much easier to take, and our kids loved them! To take us there, we hired a local guide named Linh. She took us on the public bus system for the two-hour ride to one of the two sights for the Cu Chi tunnels that was much less touristy (Ben Duoc). She was sweet, fun and knowledgeable, and our kids adored her.

The first thing we saw was the Ben Duoc Memorial Temple. It was huge, beautiful, and on the wall thousands of names of north Vietnamese soldiers (“martyrs,” they were called) who had died in the war were inscribed. Of course, I thought, there is a war memorial for U.S. vets in Washington, and a memorial for the north Vietnamese here. What about all those south Vietnamese vets? They didn’t get anything.

At the tunnels we had two different guides to lead groups of us to two different portions. In the form of full exhibits with manikins, the first portion showed us the village and how people lived, from servant up to the mayor of town.

We learned the tunnels were 250 km. long and took 20 years to build, starting in 1948, and some went three stories deep. Everyone, old or young was required to build them. All they used was a small shovel and woven basket.

Then we had a second guide for a tour of the actual tunnels. He spoke English and had a great sense of humor. He joked that even the guy with the beer belly could fit, as the tunnels had been widened for tourists. He showed us various tunnels that both our kids were excited to go through. It’s hard to imagine, but the Vietcong pretty much lived in these tunnels during the war.

We also learned that many died in the tunnels from diseases (malaria, for example), which is not hard to imagine in this tropical region. The guide had showed us a tube that would bring in air, as well as water if it was raining. Another guide admitted that about 80% of the tunnels have been destroyed since then.

No matter, our kids had loads of fun crawling through them with flashlights, along with the rest of our group. They made no real connection between these tunnels and the slaughter of war. Maybe, for now, it’s better that way.

We were happy to end our day with Linh, our hired guide, at a restaurant in HCMC that specializes in food from central Vietnam. Linh has traveled a lot, although she has not yet been to the United States, where one of her uncles who had fought in the war for the south now lives. It’s not so easy for Vietnamese to get visas to the U.S. I find it fascinating, though, that what she does now for a living (her “day” job) is to help Vietnamese investors locate investment projects, such as building schools, hotels, apartments, or infrastructures (such as train systems), in the U.S. Vietnamese who invest at least $500,000 in such properties can usually secure temporary green cards.

We end up learning a lot about Vietnam through the stories people tell us. In HCMC, for example, one young Vietnamese man who wished to remain anonymous told us, “Our family was rich. We had a lot of property. But the north came and took it all away and gave it to other people.” He didn’t seem angry, more matter of fact about it. (Here’s more on the land reforms that took place, if curious.)

As we traveled the length of Vietnam in coming weeks, we would hear many more stories with many viewpoints—all becoming part of the deep textured fabric that is Vietnam today. This country has definitely come a long way since its war with the Americans.

This blog post, including photos, is copyrighted (c) 2016 by Cindy Bailey and is an original publication of www.mylittlevagabonds.com. Please join us on Twitter and Facebook. Happy travels!

I must say that I learned more from you then 10th grade history!!!! Very informative and your children are getting such an education. Keep writing, I am loving reading about your adventures!

Ha! Thanks, Sandi!

Wonderful article, as usual. I just love hearing your stories. You do such a good job of capturing all the different angles. The war museum must have been incredibly difficult to see.

Thanks, Betty! The exhibits at the war museum were very difficult to see, but also important, I felt.